..... ..... The nature of the mind

Inside the Zen gardens of Shunmyo Masuno

By KAREN A. FOSTER

The Japan Times: Aug. 31, 2005

(C) All rights reserved

http://www.japantimes.co.jp/cgi-bin/getarticle.pl5?fa20050831a1.htm

This is a safekeep copy only.

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Shunmyo Masuno calls his works "expressions of my mind," and they have the power to stir up depths of emotion and even tap into the subconscious. They are not psychedelic paintings, however, nor are they virtual reality installations -- they are gardens. And the man who creates them is a Buddhist priest.

Known for his strikingly contemporary Japanese garden designs, Masuno, the 52-year-old head priest of Kenkoji Temple in Yokohama, is one of the world's leading landscape designers. These days, many people are designing Japanese gardens both in Japan and around the world, and the priest has seen many excellent examples of landscape design.

None of them, however, has the greatness of a Zen garden, which, he adds matter-of-factly, requires the creator to be a full-time practitioner of Zen Buddhism. Therefore, what is called a modern Zen garden these days, he said, is likely to be an imitation.

The powerful energy emanating from a Zen garden comes from the spiritual practice that went into its creation.

"The [Zen] garden teaches me something," said the 18th-generation priest. "It has a very strong arrangement and strong tension.

"A Zen garden is very calm and very strong. If you sit in front of the garden you just see," he said, pointing out the small strolling garden in Kenkoji, which he helped build at the age of 16 under the direction of famed landscape designer Katsuo Saito, to illustrate his point.

Because the practice of Zen Buddhism is largely meditative, priests are expected to take up one of the traditional arts to communicate their spiritual experiences to others. The results of many 14th- and 15th-century priests' artistic practices can still be seen in the great gardens of Kyoto.

But the days of the ishidateso (priests who design gardens) are long over. Now, priests keep their creative works on a smaller scale, doing ikebana, calligraphy and sumi-e paintings. Masuno is the only priest engaged in garden design.

Masuno said he was initially "shocked" into an interest in gardening when he saw the beauty of the ordered gardens in Kyoto as a child. Until then, his exposure to gardens had been limited to his family's temple where the plants grew wild. Masuno said he was initially "shocked" into an interest in gardening when he saw the beauty of the ordered gardens in Kyoto as a child. Until then, his exposure to gardens had been limited to his family's temple where the plants grew wild.

His interest grew stronger and he went on to study at Tama Art University in western Tokyo, where he is now a professor, and later apprenticed for five years under designer Saito. He also completed his training to become a priest, always knowing that he would follow in his father's footsteps.

He went on to design what he calls "three-dimensional art" across Japan, in a wide range of places, including the National Research Institute for Metals in Ibaraki Prefecture; Imabari International Hotel in Ehime Prefecture; and the new Ministry of Foreign Affairs complex in Tokyo, due to be completed later this year.

His gardens can also be found in such distant parts of the globe as Germany, Canada, Norway, the Philippines and Papua New Guinea.

His gardens have caused a quiet sensation. He is by no means an international star, but those who know his work look upon him with a kind of awe. While he has been the focus of magazine articles and television programs, and his work has been featured in several books on design, he doesn't go looking for publicity or high-profile jobs. These days many of his projects come to him.

"It's a very Buddhist type of thing, of working on the project and not thinking of the world around him," said Don Vaughn, a top Canadian landscape architect. "He is probably one of the greatest landscape architects in the world today."

While he calls it art, Masuno's focus is spiritual engagement and not cathartic release. He also distances himself from the business aspects of the projects, leaving those to his younger layman brother, Yoshi, who runs his company, Japan Landscape Consultants Ltd., founded in 1982. While he calls it art, Masuno's focus is spiritual engagement and not cathartic release. He also distances himself from the business aspects of the projects, leaving those to his younger layman brother, Yoshi, who runs his company, Japan Landscape Consultants Ltd., founded in 1982.

Nature for a busy world

Masuno says he feels it is his responsibility to give visitors to his gardens a place -- and an experience -- that will reinvigorate the spirit, particularly for the highly stressed city dweller.

"I always think about the type of people who will use or visit this garden or this space. For instance, in Tokyo most people are very busy with business and other things in their schedules, so for them I always think about how people relax and forget about work and how do they return [in their minds] to nature," he explained. "This is my starting point."

While he has received accolades for his more orthodox gardens -- Nitobe Memorial Garden, in Vancouver, Canada, considered one of the top three Japanese gardens in the world outside of Japan and Yuusien Garden in Berlin's sprawling Marzahn Erholungs Park, for which he received the Special Prize from the German Design Gala Spa Award -- his most striking designs are his karesansui (dry-landscape gardens), in which stones and gravel are used in place of water.

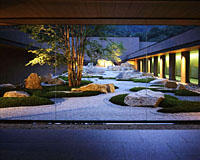

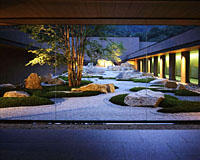

"I like to do karesansui with modern architecture. The old style of karesansui doesn't match concrete, glass and stone and metal," he said. He explained that he begins a design by asking the question: What kind of karesansui will match the modern building? "And the Canadian [Embassy] garden was one of my answers," he said. "I like to do karesansui with modern architecture. The old style of karesansui doesn't match concrete, glass and stone and metal," he said. He explained that he begins a design by asking the question: What kind of karesansui will match the modern building? "And the Canadian [Embassy] garden was one of my answers," he said.

The garden, which was completed in 1991, is wrapped around the fourth-floor reception of the Canadian Embassy in Tokyo and combines his impressions of the landscapes and peoples of Canada and Japan.

When working abroad, Masuno must teach his foreign team members about the principles of Japanese garden design. He must explain how a Japanese garden is a representation of the wilderness, but should not look artificial or obviously contrived.

"So many designers and consultants take me to a quarry. [But] I don't want to use broken stones," Masuno said. "I want a stone with a natural surface exposed to the rain and the wind for a long time. But they think, 'Stones? Oh, there are so many stones in the quarry.' But no, I want it to be natural. [They say,] 'Oh, but this is natural, not artificial stone.' "

Gerald Rainville, who studied under Masuno and is now his agent in Canada, is amazed at the clarity of the priest's vision: He sees and feels all the elements of the garden as he is constructing it. "When we go looking for a rock, he has a drawing in his mind," he said.

Vaughn, who has known Masuno for nearly 30 years, said Masuno's ability comes from his Zen training.

"What he is able to do is very difficult calculations subconsciously," Vaughn said. "Through meditation and clearing of the mind, he is able to see the answer."

The strength of Masuno's vision, and his quiet determination to carry out his task, was what won over officials at the Canadian Museum of Civilization, who thought that building a garden on the roof of their new building in Hull, Quebec, in the middle of winter was simply impossible.

Vaughn, the project's team leader, recalls Masuno's resolve in the face of local engineers who said the roof couldn't bear the weight of the rocks. But to the amazement to everyone involved, the area enjoyed record warm weather during construction and the roof is still handling the load.

It is that garden which led to Masuno's receiving in May a Canadian Meritorious Service Medal, honoring him for increasing Canadians' understanding of Japanese gardens and contributing to Canada-Japan relations.

Part of the whole

Some of the Zen priest's designs are so modern they are hardly recognizable as gardens at all. Masuno said that while the aesthetics are the same, a garden must reflect the environment in which it is created. The old gardens were built to reflect a world in which people sat on tatami mats and lived in wood and paper houses. Today, Japanese sit on chairs, surrounded by concrete and glass.

"Gardens should be changed by architecture and lifestyle -- change with everything. But the value of beauty and the atmosphere of Japanese gardens never changes," he said. "So I want to keep that basic idea, basic beauty. I want to make a garden suitable for modern architecture."

When working on a project, he consults extensively with the client and the architect so the garden and building are fully integrated. He views his work not as an adjunct to a structure but as one component of the whole. For Masuno, a building is not complete without a garden.

"In that kind of project [when a building is being constructed], we always collaborate with the architect. I make an image of the space and discuss my sketch with the architect or just talk about what I want to construct, what kind of atmosphere I want to make," he explained. "Sometimes I change the interior [of the building] drastically or sometimes I take an element of the interior outside into the garden."

The spectacular lobby at the Cerulean Tower Tokyu Hotel in Tokyo's Shibuya Ward is one of the results of that collaborative process. From all points in the circular lobby with a sunken lounge, guests have an unobstructed view of the narrow, steep garden.

"I designed the lobby lounge interior [in the Cerulean] with the garden because my basic idea was the garden outside and the interior should be one atmosphere, just as with traditional Japanese houses in which nature is connected with the people who sit inside on the tatami," he said.

Masuno is also affected by culture and environment when he works abroad. He always works with local landscape designers and horticulturists, and uses plants and rocks from the region where the garden will be situated so he can create a garden that will remind people of their particular natural world.

What remains constant is his practice.

"Basically, how I make the stone arrangement, that is completely the same," Masuno said. "Always I communicate with the stone, with plants: 'What do you want me to do? How do you want to be set up?' That communication is basic."

Everything has a purpose

His projects might look highly stylized, but every element in Masuno's gardens has its own specific place and purpose, independent of any design theory. He compares the placement of rocks to the position of bones in our bodies. The placement must be precise or the garden will not function the way it is supposed to.

"If you simply assemble a group of imperfect objects, you will not get appealing results. If you don't allow any compromises in each object when creating a space then you will create a very strong tension [in the garden]," he said. "That is why it is extremely important to pay attention to the details, even though you might think it is only cosmetic. It is very important when placing the rocks and planting trees in the garden."

As you might expect, Masuno exudes calm and confidence, and is completely focused on his work, whether it is building a garden, teaching, writing or tending to the needs of his community.

Despite the fact that there is a growing interest in his work, he said Japanese people are losing touch with Zen. Many young people want to learn about Japanese garden design these days and Masuno has taken on six apprentices. But they don't want to practice Zen.

"My students and my apprentices are very curious about Zen, but the training is very hard so they don't want to do the training," he said. "Most people understand with their minds. Young people think that knowledge is enough. . . . I think the entire country is like that."

In Western design, too, Zen has also become extremely popular. But, with a touch of frustration in his voice, Masuno said it is only fashion. People equate Zen with simplicity and minimalism, but they are not the same.

"The end result is simplicity, but in Zen the approach is very philosophical, to express the spirit and respect the material of nature. [It is] how to draw out the spirit of each material: trees, rock and wood -- to encounter them from the depths of heart."

A stroll through the basics of Zen gardening

There are three common types of Japanese gardens:

Karesansui (dry-water garden): The garden is an arrangement of rocks, gravel and moss with a specified viewing point. The style was created by Zen Buddhist priests for meditation. The garden is meant to be meditated upon infinitely.

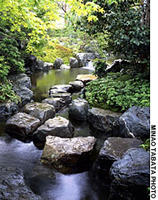

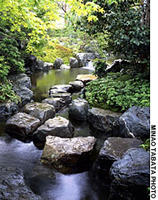

Tsukiyama (strolling garden): As its name indicates, the visitor wanders through carefully placed paths. It is intended to draw the visitor to contemplate nature outside the garden.

Chaniwa (tea garden): The garden's focus is the tea house and traditional tea ceremony.

The following are typically found in a Japanese garden:

Ishi (rock): The founding principle is that the rocks are the bones of the garden, and as such, their placement is essential to the garden's unity.

Shokubutsu (plants): The plants, both deciduous and perennial, are native to the region. While the rocks show time's permanence, the plants illustrate the passing seasons.

Mizu (water): Water is often present or represented by rock and gravel, as in karesansui.

A Japanese garden is usually an enclosed space to show a separation from the wilderness outside and ensure that the garden's atmosphere is undisturbed. If there is a significant view that can be seen from the garden it will be included as a "borrowed landscape."

The Japan Times: Aug. 31, 2005

(C) All rights reserved

|